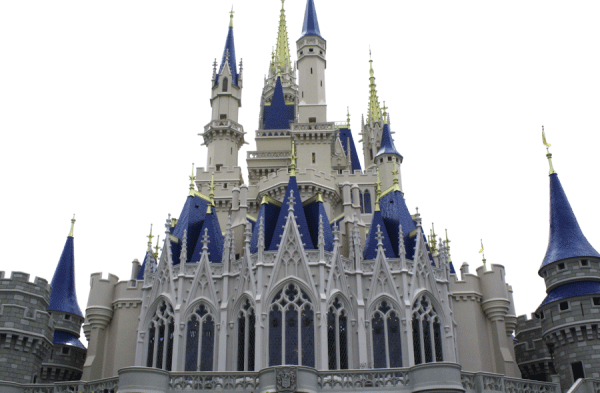

Defending Your Castle: Building Cognitive Reserve with Neurofeedback

So, three castles: the first is built of stone on the traditional model. Same slits for arrows, a little crenellation and a nice moat with ducks.

So, three castles: the first is built of stone on the traditional model. Same slits for arrows, a little crenellation and a nice moat with ducks.

A contingent of serfs and knights, sitting around eating turkey legs and repeating the jester’s jokes. Badly. Second castle’s really big, heavy with redundancies. Two moats, a couple of extra walls. Still on the traditional model, just more of everything. Third castle? Same. Except it’s clearly cleverer. Someone’s an improver, learning new things. The knights and serfs, well, they’re doing calisthenics and mock-jousting and trying new ways to smoke turkeys so they keep longer. They work smart.

Needless to say, when the invading hordes come, they make short work of the first castle, struggle with the second, and have serious trouble even making a dent in the third.

You’re born with a kind of castle in your head: a brain genetically sized and then given good nutrition and an enriched environment (or not) that makes for “brain reserve”—excess neurons, or neuronal or synaptic redundancies. No one knows how much nature and how much nurture makes for bigger castles, only that whatever nature gave you gets influenced by environment. When your brain’s attacked by disease or assault, as in traumatic brain injury or brain aging, sometimes it’ll protect itself with its redundancies.

But the third castle? More is great, but using that more cleverly, efficiently, is obviously better. Every brain has a “cognitive reserve,” too—built-up creativity that it can mine for work-arounds and re-routings.

So here’s how your brain’s cognitive reserve “works”. Say the third castle’s tower falls. An extra tower helps, but maybe you don’t have one or you need that tower for later. So you get creative; you make do. You shore up the walls and devise a smart strategy without the tower.

The better your cognitive reserve, the more likely you can find that work-around, over and over again, and not be slowed by the assault.

When they’re injured, brains can rewire, reassign tasks, relearn them, reinterpret them, sometimes so creatively and seamlessly that the problem’s imperceptible.

Scientists believe brain training affects cognitive reserve and that it’s enhanced by lifelong learning. Even though we all have brains that can create efficiencies in the face of traumatic brain injury or disease, we can make deeper, richer, more capacious reserves and survive, thrive even, if we can help our brain work more efficiently. We can brain train our way into making any brain assault less devastating.

We can do this by training our nervous system. Neurofeedback can help because it shows us our brains at work. Connects us to more effective strategies for learning and thinking. It calms and focuses our nervous energy so we get out of the way of our brain’s latent creativity.

And so when you’ve been tackled six times in a row, or you end up rear-ended and whip-lashed at the stoplight, or even defended the castle from barbarians at the gate, the smart play is to train your brain with neurofeedback machine to help negotiate any incoming siege. Which, you have to admit, is pretty cool.

Photo credit: WDWParksGal-Stock.deviantart.com

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.